(setting--kids are tidying their rooms because friends are coming over later. Breakfast is being ladeled into bowls.)

MayMay: Mom, can we have breakfast right now? We're almost done cleaning.

NSG: What's left?

MayMay: We just have to sweep.

NSG: sweep? I never said they had to sweep. When was the last time they ever swept? Well, better not to look a gift horse in the mouth... Just maybe hurry and sweep, then you'll be done!

MayMay: *nods solemnly, grabs broom and dustpan*

Jaws: Can I do that part? (pointing at the dustpan)

MayMay: No, you should sweep. I swept last time, and the time before. *considers as they head up the stairs* well, maybe we can take turns sweeping.

NSG: (tempted to pinch herself to make sure she's in the right universe they've been sweeping? Did I just not ever notice?)

(setting: NSG has sorted laundry into various baskets so the kids can put it away in their closets)

Squirt: Mom, I'll put my clothes away. Can I have a penny?

NSG: No, you only get pennies for extra jobs. This is a normal job.

Squirt: OK. *pushes the laundry basket across the floor to his room*

Squirt: *returning several minutes later* OK mom. I want an extra job.

NSG: You put your clean clothes away?

Squirt: Yup.

NSG: You didn't just throw them on the floor?

Squirt: Nope.

NSG: (walks into squirts room and stares for a moment with amazement at clean floor, opens drawers to find them filled with clean clothes) good job, Squirt!

Squirt: Can I have an extra job now?

NSG: Um. OK. Take the towels and put them in the closet.

Squirt: *returning a moment later* OK. Now what?

NSG: take the washcloths and bring them down to the kitchen drawer.

Squirt: *returning a moment later* OK. Now what.

NSG: Um... take Hazel's clothes and put them in her drawer. (watches as squirt grabs armfuls of frilly pink baby clothes and stuffs them in the drawer, getting red-faced as he unsucsessfuly tries to close the drawer on heaping mound of clothes emerging from top. Goes to help him redistribute.)

Squirt: *looks up, bright-eyed with triumph* the stuff's all put away.

NSG: Yup.

Squirt: can I have a penny?

NSG: How about a nickel? That's like five pennies.

Squirt: (squints) OK. A nickel. But not a knuckle samwhich.

NSG: What?

Squirt: A nickel, not a knuckle samwich. That's bad. That's like this (makes fist, propels it through the air, intense frown on face). It's where you punch people.

NSG: OK. Here's a nickel. Not a knuckle sandwich. And here's a little jar to keep it on, on your shelf. Thank you for helping me put away the laundry.

Squirt: (not listening...already running toward room, jingling his nickle in the jar).

Oct 31, 2011

Oct 25, 2011

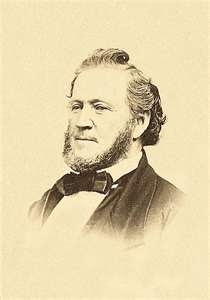

Four Hard Men, Four Different Ways: Erastus Snow

Erastus Snow, the second of my "Hard Men," wasn't hard in the same sense that Daniel W. Jones was. He didn't ever lead a 'rough and rowdy' existence. In fact he was the picture of scholarly refinement. Like his sister Eliza, who is famous for her poems and colorful, romanticised accounts of church history, he had a way with words. And like Eliza's, his accounts have been edited by family members for clarity at times.

Erastus was closely associated with both Joseph Smith and Brigham Young. He was a leader of men and organizer of movements. A man who obeyed, and lead. A hard worker and cool-headed in an emergency, he was often put in charge of exacting tasks: opening the mission in Scandinavia, translating the Book of Mormon into Danish, founding colonies in three different, inhospitable places. He survived the Mormon persecutions--all the way from Kirtland to Nauvoo.

He was a well-written, articulate man. Made the best of things, tried not to complain. Deliberate, cool-headed, and analytical, he nevertheless believed deeply in Joseph Smith and Brigham Young as prophets of god. He was very spiritual, exercized his priesthood and paid attention to his family, large as it was.

Erastus loved his family. There were two wives and three children at the time of the crossing to the Salt Lake Valley; Minerva and Artimesia, and Erastus was 28 at the time. At the time of his death, he had at least 4 wives and 36 children.

He was interested in people. He connected especially with spirituality and spiritual experiences of those around him, but he was also interested in science. The Snows were, as those who study Mormon history know, a scholarly family. Eliza was a prolific reader and writer and was later dubbed the "poetess of zion," and Lorenzo, who would become the fifth presiden of the church, was described as "bookish," pursuing education even to the first year of college, which was very uncommon for someone of the farming class. And then there was Zerubabbel. In addition to scholarly pursuits, the family had a tradition of eccentric names, a tradition that runs common in the LDS faith and continues even today. (My new neighbor's first name is Daedree. Pronounced kind of like daydream. I try hard not to call her that by accident.) (And I think there is more than one "LaVerle" in my ward.)

Anyway, Erastus's fascination with humanity had a kind of anthropologic bent. He was very interested in people, and remembered details about everyone he met. And he was fascinated by the Indians. A few accounts from his writings:

"....As soon as they saw our flag they began to cross the river towards us. We took the precaution to stake down our horses and admitted at first only the chief to our camp, but afterward the whole of them. They had their squaws with them and camped about half a mile from us, and visited us again in the morning. They were all dressed in their richest costumes. Some had fur caps and cloth coats, and others had cloth pants and shirts, and the rest were neatly dressed in skins ornamented with beads, feathers, paint, etc., and they were by all odds the cleanest and best appearing Indians we have seen west of the Missouri river. Some of the brethren traded horses with them and bought some peltry, moccasins and other trinkets, and they crossed the river apparently in high glee, and we pursued our journey." From The Diary of Erastsus Snow, edited by his son, Moroni.

And another:

"This is the country of the Snake Indians, some of whom were at the fort. They bear a good reputation among the mountaineers for honesty and integrity. We traded some with the traders at the fort, and with the French and Indians that were camped near there, but we found that their skins and peltry were quite as high as they were in the states, though they allowed us liberal prices for the commodities we had to exchange." (Diary of Erastus Snow, linked above).

You see here that Snow's attitude toward the Indians was an observant, somewhat detached one... interested in how they were different. Perhaps a little condescending at times.

Another passage from his diary:

"During this week the Ute and Shoshone Indians visited our camp in small parties, almost daily, and traded some horses for guns and skins for clothing, etc. They seemed much pleased at our settling here. While here, one of the Utes stole a horse from the Shoshones and was pursued up the valley by the latter and killed, and his comrade and their horses and the victors returned to our camp with the stolen property.

The following Sunday, August 1st, a resolution was adopted in camp to trade no more with the Indians except at their own encampment, and hold out no inducements to their visiting our camp."

And,

"Sunday morning, October 2, while the camp was starting, a high-spirited Spanish mare which I had purchased of Mr. Racheau unhorsed her rider and at the top of her speed, which was like the flight of a hare, pursued an Indian hunting party that was at that time crossing the bottoms some miles distant towards the bluffs, and although I pursued upon my windiest horse I had a ride of about fifteen miles before I could catch her again. This unlucky circumstance threw me into the midst of what was to me quite a romantic scene—a regular Indian buffalo hunt. When the party arrived in the vicinity of some scattering herds they separated into parties of two and three and took their stations upon tops of buttes or eminences in the prairie in all directions for several miles, so that they could see the direction the herd was taking in the flight. Then two Indians started the herd and pursued in the rear while others were intercepting their retreat and, selecting the fattest cows, let fly their arrows (for they use no firearms in this chase) which seldom failed to do execution; and if the first was not sufficient, the second and third arrow quickly followed, and once wounded became the sole target for the Indian’s arrows until the victim fell. Turn which way they would the herd was sure to be attacked by a fresh party of horsemen who in turn would strew the ground with the slain. When the herd had thus run the gauntlet for some four or five miles and the chase was abandoned, the Indians could be seen in all directions dressing their game. I passed one who had been unhorsed and broken his arm in the chase and his squaw was splintering it up. An old Indian presented me with a couple of tongues which with them is the choicest part of the buffalo, and I returned to camp gratified by the scene I had witnessed and scarcely regretted the chase I had for my mare."

Erastus's account of his dealing with the Indians paints a sort of black-and-white picture. There were, to him, "good indians," childlike, willing to be peacable and taught, and "bad indians," who stirred up trouble, were "bloodthirsty," stole things. And often he excuses these "bad" indians, noting that likely they'd been fed lies about the Mormon settlers by preceding companies, or were being "stirred up" by someone against the church.

One more passage, I thought, was particularly revealing. This comes from an address Erastus Snow gave at a conference in Logan, six years before his death. The address was all about the Indians and how the Mormon settlers had influnced them.

"If the Spirit gives me liberty I will pursue the train of thought that has passed through my mind while Brother Richards has been speaking upon

the spirit that has gone abroad upon the remnants of the house of Israel who occupy this land, the American Indians whom we understand to be the descendants of the Nephites, the Lamanites, the Lemuelites and the Ishmaelites who formerly possessed this land, whose fathers we have an account of in the Book of Mormon....we have chastised them when it became necessary to do so, not in malice nor revenge, but as a father would chastise his wayward child, and then as soon as possible pour into their wounds the oil and the wine to heal them up again—those, I say, who are best acquainted with our labors in this direction will best appreciate the results."

And there is the clincher. Right there. Why did Erastus Snow see the Indians as people? They were descendents of the people in the Book of Mormon. His feeling, his "mission" among the Indians, had very much to do with this, and with the desire to help fulfill the prophecy Joseph Smith made at one time about the Lamanites "blossoming as a rose."

Nowadays, such an attitude would of course meet with resistance and be called prejudice. But you have to give Snow props for how his attitude diverged hugely from the attitude of the times. And for his own feelings... he really loved people. And to him, Indians were people...on the level of children, which could seen to be rather condescending, but you have to remember that he was a product of his time. He did see them people, not animals or savages as the majority of settlers and emigrants at the time seemed to believe.

As I read and looked for clues in these histories and accounts of what sort of man Erastus was, I was struck, over and over, by his complete acceptance of everything Joseph Smith or Brigham Young, or any other prophet, had to say. He loved the presidents of the church, and strove to emulate them. You might go so far as to say he adopted a great deal of their ideas, and even persona. In fact, here is an interesting phenomenon. Let me know if you see it... maybe it's just me...

Erastus Snow

Brigham Young

Erastus Snow

Brigham Young

Erastus Snow

I think Erastus saw himself as an extension of the Prophet, and of the church. There are a few references to him in histories as a "prophet" or "prophetic."

Because of who Erastus was--how spirituality was such a focus of his life, how he felt so devoted to the prophets and the LDS gospel, It is possible that Erastus Snow's views of the Indians could be said to echo, or even duplicate those of the church at the time.

Erastus was closely associated with both Joseph Smith and Brigham Young. He was a leader of men and organizer of movements. A man who obeyed, and lead. A hard worker and cool-headed in an emergency, he was often put in charge of exacting tasks: opening the mission in Scandinavia, translating the Book of Mormon into Danish, founding colonies in three different, inhospitable places. He survived the Mormon persecutions--all the way from Kirtland to Nauvoo.

He was a well-written, articulate man. Made the best of things, tried not to complain. Deliberate, cool-headed, and analytical, he nevertheless believed deeply in Joseph Smith and Brigham Young as prophets of god. He was very spiritual, exercized his priesthood and paid attention to his family, large as it was.

Erastus loved his family. There were two wives and three children at the time of the crossing to the Salt Lake Valley; Minerva and Artimesia, and Erastus was 28 at the time. At the time of his death, he had at least 4 wives and 36 children.

He was interested in people. He connected especially with spirituality and spiritual experiences of those around him, but he was also interested in science. The Snows were, as those who study Mormon history know, a scholarly family. Eliza was a prolific reader and writer and was later dubbed the "poetess of zion," and Lorenzo, who would become the fifth presiden of the church, was described as "bookish," pursuing education even to the first year of college, which was very uncommon for someone of the farming class. And then there was Zerubabbel. In addition to scholarly pursuits, the family had a tradition of eccentric names, a tradition that runs common in the LDS faith and continues even today. (My new neighbor's first name is Daedree. Pronounced kind of like daydream. I try hard not to call her that by accident.) (And I think there is more than one "LaVerle" in my ward.)

Anyway, Erastus's fascination with humanity had a kind of anthropologic bent. He was very interested in people, and remembered details about everyone he met. And he was fascinated by the Indians. A few accounts from his writings:

"....As soon as they saw our flag they began to cross the river towards us. We took the precaution to stake down our horses and admitted at first only the chief to our camp, but afterward the whole of them. They had their squaws with them and camped about half a mile from us, and visited us again in the morning. They were all dressed in their richest costumes. Some had fur caps and cloth coats, and others had cloth pants and shirts, and the rest were neatly dressed in skins ornamented with beads, feathers, paint, etc., and they were by all odds the cleanest and best appearing Indians we have seen west of the Missouri river. Some of the brethren traded horses with them and bought some peltry, moccasins and other trinkets, and they crossed the river apparently in high glee, and we pursued our journey." From The Diary of Erastsus Snow, edited by his son, Moroni.

And another:

"This is the country of the Snake Indians, some of whom were at the fort. They bear a good reputation among the mountaineers for honesty and integrity. We traded some with the traders at the fort, and with the French and Indians that were camped near there, but we found that their skins and peltry were quite as high as they were in the states, though they allowed us liberal prices for the commodities we had to exchange." (Diary of Erastus Snow, linked above).

You see here that Snow's attitude toward the Indians was an observant, somewhat detached one... interested in how they were different. Perhaps a little condescending at times.

Another passage from his diary:

"During this week the Ute and Shoshone Indians visited our camp in small parties, almost daily, and traded some horses for guns and skins for clothing, etc. They seemed much pleased at our settling here. While here, one of the Utes stole a horse from the Shoshones and was pursued up the valley by the latter and killed, and his comrade and their horses and the victors returned to our camp with the stolen property.

The following Sunday, August 1st, a resolution was adopted in camp to trade no more with the Indians except at their own encampment, and hold out no inducements to their visiting our camp."

And,

"Sunday morning, October 2, while the camp was starting, a high-spirited Spanish mare which I had purchased of Mr. Racheau unhorsed her rider and at the top of her speed, which was like the flight of a hare, pursued an Indian hunting party that was at that time crossing the bottoms some miles distant towards the bluffs, and although I pursued upon my windiest horse I had a ride of about fifteen miles before I could catch her again. This unlucky circumstance threw me into the midst of what was to me quite a romantic scene—a regular Indian buffalo hunt. When the party arrived in the vicinity of some scattering herds they separated into parties of two and three and took their stations upon tops of buttes or eminences in the prairie in all directions for several miles, so that they could see the direction the herd was taking in the flight. Then two Indians started the herd and pursued in the rear while others were intercepting their retreat and, selecting the fattest cows, let fly their arrows (for they use no firearms in this chase) which seldom failed to do execution; and if the first was not sufficient, the second and third arrow quickly followed, and once wounded became the sole target for the Indian’s arrows until the victim fell. Turn which way they would the herd was sure to be attacked by a fresh party of horsemen who in turn would strew the ground with the slain. When the herd had thus run the gauntlet for some four or five miles and the chase was abandoned, the Indians could be seen in all directions dressing their game. I passed one who had been unhorsed and broken his arm in the chase and his squaw was splintering it up. An old Indian presented me with a couple of tongues which with them is the choicest part of the buffalo, and I returned to camp gratified by the scene I had witnessed and scarcely regretted the chase I had for my mare."

Erastus's account of his dealing with the Indians paints a sort of black-and-white picture. There were, to him, "good indians," childlike, willing to be peacable and taught, and "bad indians," who stirred up trouble, were "bloodthirsty," stole things. And often he excuses these "bad" indians, noting that likely they'd been fed lies about the Mormon settlers by preceding companies, or were being "stirred up" by someone against the church.

One more passage, I thought, was particularly revealing. This comes from an address Erastus Snow gave at a conference in Logan, six years before his death. The address was all about the Indians and how the Mormon settlers had influnced them.

"If the Spirit gives me liberty I will pursue the train of thought that has passed through my mind while Brother Richards has been speaking upon

the spirit that has gone abroad upon the remnants of the house of Israel who occupy this land, the American Indians whom we understand to be the descendants of the Nephites, the Lamanites, the Lemuelites and the Ishmaelites who formerly possessed this land, whose fathers we have an account of in the Book of Mormon....we have chastised them when it became necessary to do so, not in malice nor revenge, but as a father would chastise his wayward child, and then as soon as possible pour into their wounds the oil and the wine to heal them up again—those, I say, who are best acquainted with our labors in this direction will best appreciate the results."

And there is the clincher. Right there. Why did Erastus Snow see the Indians as people? They were descendents of the people in the Book of Mormon. His feeling, his "mission" among the Indians, had very much to do with this, and with the desire to help fulfill the prophecy Joseph Smith made at one time about the Lamanites "blossoming as a rose."

Nowadays, such an attitude would of course meet with resistance and be called prejudice. But you have to give Snow props for how his attitude diverged hugely from the attitude of the times. And for his own feelings... he really loved people. And to him, Indians were people...on the level of children, which could seen to be rather condescending, but you have to remember that he was a product of his time. He did see them people, not animals or savages as the majority of settlers and emigrants at the time seemed to believe.

As I read and looked for clues in these histories and accounts of what sort of man Erastus was, I was struck, over and over, by his complete acceptance of everything Joseph Smith or Brigham Young, or any other prophet, had to say. He loved the presidents of the church, and strove to emulate them. You might go so far as to say he adopted a great deal of their ideas, and even persona. In fact, here is an interesting phenomenon. Let me know if you see it... maybe it's just me...

Erastus Snow

Brigham Young

Erastus Snow

Brigham Young

Erastus Snow

I think Erastus saw himself as an extension of the Prophet, and of the church. There are a few references to him in histories as a "prophet" or "prophetic."

Because of who Erastus was--how spirituality was such a focus of his life, how he felt so devoted to the prophets and the LDS gospel, It is possible that Erastus Snow's views of the Indians could be said to echo, or even duplicate those of the church at the time.

Oct 19, 2011

motherly heartache

I haven't officially told this to the world yet: The Nosurf family will be welcoming its seventh child into the world on or around March 3, 2012.

OK, so, now that's out of the way...

I've been weaning baby Rose.

Baby Rose hasn't gotten a whole lot of publicity on here. MOstly because I took a big break when we moved, and she's only been around for 18 months. But she is very intelligent, flower-faced, large-blue-eyed, and has the ability to make great stern/and or bright smiley faces. She experiments sometimes, sitting in my lap and gazing at me sternly for a moment, then breaking into a smile that would take anyone's breath away and flinging herself against my torso, patting my back.

She also says stuff now.

Her newest language acquisition is the word "Why."

I'll say no more snack,she'll look at me, wide eyed...

Baby Rose: Why?

NSG: Because you just had six crackers, half a peanut butter sandwich and some yogurt. You don't need more food until lunch.

Baby Rose: (Frowning with intense concentration)Ukay. (walks off.)

This is a fun exchange... cute, heartwarming, delightful. Not so fun is this:

Baby Rose: (pointing at my shriveled, depleted mammary organs) Nana? Nana?

NSG: (Attempts a smile) All gone!

Baby Rose: (eyes slowly fill with tears, mouth trembles) Why?!

NSG: because my poor excuse for a body can only produce enough milk and nutrients for *one* child and you, flower baby of my heart, are being supplanted. Because it's all gone, Baby. I'm so sorry.

Baby Rose: (crying now) Why?

NSG: I'm sorry baby.

Lots of hugging and cuddling with baby rose, but lately... very little nursing. And I don't know why, but I don't feel relieved this time like I did with my last few. I feel sad. I don't want to say any time is the "last time." I suddenly realize that there is a level of closeness that goes away when the nursing goes away, and I can't just bring myself to end it, in spite of the fact that when we do nurse, Baby Rose nuzzles with increasingly more frustration, pulls away, cries, asks for the other side, finds it similarly depleted, pulls away, cries...

Why am I having such a hard time with this particular milestone? Do I love this baby more than I did the others? No.

It could be all the changes. Rose has been a comfort to me, and to our whole family. She is the sister that all of my kids, bio and adopted, "Share." She was in mommy's tummy, and born, when everybody was here. She has been babied more than any of my other babies ever were, by everybody. Maybe there is something especially sweet about a baby that knows she is the princess, the apple of everbody's eye... about an 18-month old who knows she can make someone happy by smiling at them.

I'm struggling with this weaning in a way I never anticipated I would... and it's making it harder for me to get excited about this new little one. I know I'll get over it, but for now, there's a bit of grieiving going on.

OK, so, now that's out of the way...

I've been weaning baby Rose.

Baby Rose hasn't gotten a whole lot of publicity on here. MOstly because I took a big break when we moved, and she's only been around for 18 months. But she is very intelligent, flower-faced, large-blue-eyed, and has the ability to make great stern/and or bright smiley faces. She experiments sometimes, sitting in my lap and gazing at me sternly for a moment, then breaking into a smile that would take anyone's breath away and flinging herself against my torso, patting my back.

She also says stuff now.

Her newest language acquisition is the word "Why."

I'll say no more snack,she'll look at me, wide eyed...

Baby Rose: Why?

NSG: Because you just had six crackers, half a peanut butter sandwich and some yogurt. You don't need more food until lunch.

Baby Rose: (Frowning with intense concentration)Ukay. (walks off.)

This is a fun exchange... cute, heartwarming, delightful. Not so fun is this:

Baby Rose: (pointing at my shriveled, depleted mammary organs) Nana? Nana?

NSG: (Attempts a smile) All gone!

Baby Rose: (eyes slowly fill with tears, mouth trembles) Why?!

NSG: because my poor excuse for a body can only produce enough milk and nutrients for *one* child and you, flower baby of my heart, are being supplanted. Because it's all gone, Baby. I'm so sorry.

Baby Rose: (crying now) Why?

NSG: I'm sorry baby.

Lots of hugging and cuddling with baby rose, but lately... very little nursing. And I don't know why, but I don't feel relieved this time like I did with my last few. I feel sad. I don't want to say any time is the "last time." I suddenly realize that there is a level of closeness that goes away when the nursing goes away, and I can't just bring myself to end it, in spite of the fact that when we do nurse, Baby Rose nuzzles with increasingly more frustration, pulls away, cries, asks for the other side, finds it similarly depleted, pulls away, cries...

Why am I having such a hard time with this particular milestone? Do I love this baby more than I did the others? No.

It could be all the changes. Rose has been a comfort to me, and to our whole family. She is the sister that all of my kids, bio and adopted, "Share." She was in mommy's tummy, and born, when everybody was here. She has been babied more than any of my other babies ever were, by everybody. Maybe there is something especially sweet about a baby that knows she is the princess, the apple of everbody's eye... about an 18-month old who knows she can make someone happy by smiling at them.

I'm struggling with this weaning in a way I never anticipated I would... and it's making it harder for me to get excited about this new little one. I know I'll get over it, but for now, there's a bit of grieiving going on.

Oct 18, 2011

Four Hard Men, Four Different ways: Part I, Daniel W. Jones

In trying to frame a kind of reference for discussing the relations between the Indians and the settlers in Utah Valley, I came up with the idea to discuss four men who dealt with the Indians on a frequent basis, and who, at times, were called to positions as interpreters/diplomats between the tribes and the settlers. These are four very different men, and their stories will, I think, provide a good picture.

I will start with Daniel W. Jones. A great deal of this information was taken from his autobiographical work, 40 Years Among The Indians. It is a very well-written and lively, sometimes hilarious work. The link I have provided has the full text, broken up into chapters. I suggest you go read it, or read sections of it, if this subject matter interests you.

Daniel W. Jones was born in the year 1830. He was orphaned at the age of 12. At the age of 17, he joined a group of fighters in the Mexican American war. He started out in life hard, and his life continued that way--staying in Mexico after the war to live a "wild and rowdy" existence.

Eventually he tired of that sort of fun and decided to join a sheep herding expedition. While on this expedition, he accidentally shot himself in the leg. The company left him behind, to the care of a Mormon settlement, where he was converted to the LDS faith.

He was an open-minded, warm, humorous man with a hot temper and, sometimes, a nasty defensive streak.

I don't think Daniel W. Jones was one of the first thirty families to settle in Provo, but he was there in the early years. And he took it upon himself from the beginnging to relate to the Indians and sometimes take up their cause. Accounts (other than his own history) paint him as being viewed as odd by the community--a sort of hermit, living way up on the bench above town in the middle of Indian territory in spite of the advice of Brigham Young. He describes his involvement in the Walker wars and other conflicts in this way:

"Active hostilities were kept up more or less according to opportunities during the summer of '53. When the Indians had a good chance they would steal or kill. Some were more or less peaceable when it suited them. I never went out to fight as I made no pretensions whatever of being an Indian fighter. I did my portion of military duty. I assisted in various ways in helping to protect ourselves against the natives, but I always made it a rule to cultivate a friendly feeling whenever opportunity presented; so much so that the Indians always recognized me as a [61] friend to their race.

I always considered the natives entitled to a hearing as well as the whites. Both were often in the wrong. The white men should be patient and just with the Indians and not demand of them in their untutored condition the same responsibility they would of the more intelligent class." (pp. 61, Forty Years Among the Indians)

A few years later, when Brigham Young got up and made his famous appeal in a testimony meeting for volunteers to go save the Martin and Willie handcart companies, Daniel W. Jones was among the first to agree. He rode out, met the company and found: "the hand-cart company ascending a long muddy hill. A condition of distress here met my eyes that I never saw before or since. The train was strung out for three or four miles. There were old men pulling and tugging their carts, sometimes loaded with a sick wife or children--women pulling along sick husbands--little children six to eight years old struggling through the mud and snow. As night came on the mud would freeze on their clothes and feet. There were two of us and hundreds needing help. What could we do? We gathered on to some of the most helpless with our riatas tied to the carts, and helped as many as we could into camp on Avenue hill.

This was a bitter, cold night and we had no fuel excepting very small sage brush. Several died that night." (pp. 68-69, Forty Years Among the Indians)

Daniel Jones was a practical man, a survivor. He also had a heart full of compassion. He was an ideal person to go and help the handcart companies. He stayed with them, helping them through the hardest point of their journey, a passage called Devil's Gate, and then when he was asked, he turned around and went back to the spot where the company had left all their supplies and cattle, to guard it through the winter against Indian and other attacks and thefts until the spring, when it could be brought back to the owners into the Salt Lake Valley. Daniel W. Jones and two other men were tasked with this.

"I LEFT the company feeling a little downcast," he wrote, "to return to Devil's Gate. It was pretty well understood that there would be no relief sent us. My hopes were that we could kill game. We had accepted the situation, and as far as Capt. Grant was concerned he had done as much as he could for us. There was more risk for those who went on than for us remaining. "

His account paints that winter as a very grim experience. They ate rawhide, most of the cattle were killed and scattered by the wolves or starved to death. At one point, the men with Jones looked at the fat carcasses of the wolves they had shot, and asked him if they could eat them. Jones said that they ought not to, the animals were "unclean" as a food source, and the Lord would provide them with good food if they looked to their own weaknesses and strove to be righteous in their duties. Very soon after,

"...[a]Frenchmen and Indian came into the fort with their animals loaded with good buffalo meat. I asked about the boys of our company who went out on foot. The Frenchmen answered, "I left them about twenty-five miles from here roasting and eating bones and entrails; they are all right." They got in next day, each man loaded with meat. They were all delighted with the Indian, telling how he killed the buffalo with his arrows, the Frenchmen shooting first and wounding the animal and the Indian doing the rest."

Daniel Jones made it through the winter, and brought as many of the goods across himself as he could manage. Anything in boxes was brought, most of the cattle was reported missing or stolen. Jones kept a careful account of what they used and ate and presented it to Brigham Young, who looked the account over carefully and gave it his approval.

When Jones got to Provo with the provisions for people who had ended their journey there, he found a maelstrom of rumors had been spread about him. People whispered that he had stolen. When he brought the goods to the people, a couple of them said they should have more than he gave them. Jones said he brought what was there, and that was that.

But that wasn't that. The rumors got to the point where Jones was denied entrance in the high priests, which, back then, was a political as well as priesthood leadership position. They cited his thievery as the reason. Moves began to be made by bishops to accuse Jones of the stealing, and women from the community were even telling Jones' wife to "leave him, and go find a better man."

On this matter, Jones writes: "My wife answered, "Well I will not leave Daniel Jones. I cannot better myself, for if he will steal there is not an honest man on earth." I always appreciated the answer."

It came to a head when Jones' (now many) accusers went to Brigham Young and sought a trial. Brigham Young met with Daniel W. Jones and told him that he had been accused, and asked him if he would stand trial and prove himself.

Jones describes himself as feeling shaken by this, because Brigham had previously looked over his account and approved of all he did, and expressed his satisfaction. But he agreed. He wanted to ask the prophet more questions, but Young turned away and went about some chores, not allowing him to speak.

Jones went into the trial nervous, afraid that there was nothing he could say to defend himself, if the prophet thought he was guilty. But the trial was a surprise to everybody. After asking everyone to testify, Brigham Young turned to Brother Jones and said (this is from the biography again):

"You wanted to ask me if I thought you guilty, but I gave you no chance to ask the question. I wanted you to learn that when I decide anything, as I had in your case, I do not change my mind. You were [121] not brought here for a trial for being guilty, but to give you a chance to stop these accusations." Then turning to my accusers again, "How does this look? After charging Brother Jones as you have, he makes a simple statement, affirming nothing, neither witnessing anything, and each of you say you believe he has told the truth. You have nothing to answer save that he is an honest man. Well, now, what have you brought him for?"

One of the complainers then asked if some of the company with me might not have stolen the goods. I answered "No; I am here to answer for all. Besides it would have been almost impossible for anyone besides myself to have taken anything unbeknown to others."

Bro. ______ asked, "If neither Bro. Jones nor the brethren with him have taken anything, how is it that I have lost so much?"

Brother Brigham replied, "It is because you lie. You have not lost as you say you have." (pp. 121, Forty Years Among the Indians).

After chewing out the accusers, Brigham Young and the quorum of the twelve wrote a letter of exoneration on Jones' behalf, asking that he be allowed into the high priests' counsel in Provo.

One more incident paints a perfect picture, to me, of who Daniel W. Jones was. Again, from Forty Years Among the Indians:

"One day I noticed a crowd of soldiers making some curious and exciting moves. I approached to see what was the matter. I saw an Indian standing, holding something in his hand and looking rather confused. The soldiers were getting a rope ready to hang him; all was excitement and I am satisfied that if I had not happened along the poor Indian would have been swinging by the neck in less than five minutes.

I could see from the Indian's manner that he realized something was wrong but could not understand why he was surrounded by soldiers.

I asked them what they were doing. They said that the Indian had brought one of their horses that he had stolen into camp and sold it for thirty dollars; that the owner of the horse was there and they were intending to hang the "d----d thief." I told them to hold on a minute, that I did not think an Indian would steal a horse and bring it into the camp where it belonged to sell. Some one answered, "Yes, he has; there is the money now in his hand that he got for the horse."

The Indian was still standing there, holding the money in his open hand and looking about as foolish as ever I saw one of his race look. I asked him what was up. He said he did not know what was the matter.

"What about the horse and money?"

He answered, "I found a horse down at our camp. I knew it belonged to the soldiers so I brought it up, thinking they would give me something for bringing it. This man," pointing to one, "came and took hold of the horse and put some money in my hand. It was yellow money and I did not want it. He then put some silver in my hand. There it all is. I don't understand what they are mad about."

I soon got the trouble explained. The man thought he was buying the horse, the Indian thought he was rewarding him for bringing the animal to camp; the owner happened along just as the trade was being made. Here ignorance and prejudice came near causing a great crime. As soon as this was explained I took the money and gave it back to the owner. No one had thought of taking the money. All were bent on hanging the honest fellow. Soon there was a reverse of feeling; most of the soldiers in the crowd being Irish, they let their impulses run as far the other way, loading the Indian with shirts and blouses. Some gave him money, so that he went away feeling pretty well, but he remarked that the soldiers were kots-tu-shu-a (big fools).

I have often thought there were many like these soldiers, " heap kots-tu-shu-a," in dealing with Indians."

Daniel W. Jones was a man who had a hard life, who was a survivor and hard worker, who was often thought to be odd by his neighbors. Throughout his life, he humbled himself and did what the prophets and other leaders asked of him in spite of tragedies, privations, and his own edge of pride and hot temper, which sometimes lead him to mouth off (but he always regretted it later, when he did). And somehow, all that rough exterior contained a soft heart, an open mind, and a view of the Indians as people who deserved justice just as the white men did.

Up Next: Four Hard Men, Four Different ways: Part II, Erastus Snow.

I will start with Daniel W. Jones. A great deal of this information was taken from his autobiographical work, 40 Years Among The Indians. It is a very well-written and lively, sometimes hilarious work. The link I have provided has the full text, broken up into chapters. I suggest you go read it, or read sections of it, if this subject matter interests you.

Daniel W. Jones was born in the year 1830. He was orphaned at the age of 12. At the age of 17, he joined a group of fighters in the Mexican American war. He started out in life hard, and his life continued that way--staying in Mexico after the war to live a "wild and rowdy" existence.

Eventually he tired of that sort of fun and decided to join a sheep herding expedition. While on this expedition, he accidentally shot himself in the leg. The company left him behind, to the care of a Mormon settlement, where he was converted to the LDS faith.

He was an open-minded, warm, humorous man with a hot temper and, sometimes, a nasty defensive streak.

I don't think Daniel W. Jones was one of the first thirty families to settle in Provo, but he was there in the early years. And he took it upon himself from the beginnging to relate to the Indians and sometimes take up their cause. Accounts (other than his own history) paint him as being viewed as odd by the community--a sort of hermit, living way up on the bench above town in the middle of Indian territory in spite of the advice of Brigham Young. He describes his involvement in the Walker wars and other conflicts in this way:

"Active hostilities were kept up more or less according to opportunities during the summer of '53. When the Indians had a good chance they would steal or kill. Some were more or less peaceable when it suited them. I never went out to fight as I made no pretensions whatever of being an Indian fighter. I did my portion of military duty. I assisted in various ways in helping to protect ourselves against the natives, but I always made it a rule to cultivate a friendly feeling whenever opportunity presented; so much so that the Indians always recognized me as a [61] friend to their race.

I always considered the natives entitled to a hearing as well as the whites. Both were often in the wrong. The white men should be patient and just with the Indians and not demand of them in their untutored condition the same responsibility they would of the more intelligent class." (pp. 61, Forty Years Among the Indians)

A few years later, when Brigham Young got up and made his famous appeal in a testimony meeting for volunteers to go save the Martin and Willie handcart companies, Daniel W. Jones was among the first to agree. He rode out, met the company and found: "the hand-cart company ascending a long muddy hill. A condition of distress here met my eyes that I never saw before or since. The train was strung out for three or four miles. There were old men pulling and tugging their carts, sometimes loaded with a sick wife or children--women pulling along sick husbands--little children six to eight years old struggling through the mud and snow. As night came on the mud would freeze on their clothes and feet. There were two of us and hundreds needing help. What could we do? We gathered on to some of the most helpless with our riatas tied to the carts, and helped as many as we could into camp on Avenue hill.

This was a bitter, cold night and we had no fuel excepting very small sage brush. Several died that night." (pp. 68-69, Forty Years Among the Indians)

Daniel Jones was a practical man, a survivor. He also had a heart full of compassion. He was an ideal person to go and help the handcart companies. He stayed with them, helping them through the hardest point of their journey, a passage called Devil's Gate, and then when he was asked, he turned around and went back to the spot where the company had left all their supplies and cattle, to guard it through the winter against Indian and other attacks and thefts until the spring, when it could be brought back to the owners into the Salt Lake Valley. Daniel W. Jones and two other men were tasked with this.

"I LEFT the company feeling a little downcast," he wrote, "to return to Devil's Gate. It was pretty well understood that there would be no relief sent us. My hopes were that we could kill game. We had accepted the situation, and as far as Capt. Grant was concerned he had done as much as he could for us. There was more risk for those who went on than for us remaining. "

His account paints that winter as a very grim experience. They ate rawhide, most of the cattle were killed and scattered by the wolves or starved to death. At one point, the men with Jones looked at the fat carcasses of the wolves they had shot, and asked him if they could eat them. Jones said that they ought not to, the animals were "unclean" as a food source, and the Lord would provide them with good food if they looked to their own weaknesses and strove to be righteous in their duties. Very soon after,

"...[a]Frenchmen and Indian came into the fort with their animals loaded with good buffalo meat. I asked about the boys of our company who went out on foot. The Frenchmen answered, "I left them about twenty-five miles from here roasting and eating bones and entrails; they are all right." They got in next day, each man loaded with meat. They were all delighted with the Indian, telling how he killed the buffalo with his arrows, the Frenchmen shooting first and wounding the animal and the Indian doing the rest."

Daniel Jones made it through the winter, and brought as many of the goods across himself as he could manage. Anything in boxes was brought, most of the cattle was reported missing or stolen. Jones kept a careful account of what they used and ate and presented it to Brigham Young, who looked the account over carefully and gave it his approval.

When Jones got to Provo with the provisions for people who had ended their journey there, he found a maelstrom of rumors had been spread about him. People whispered that he had stolen. When he brought the goods to the people, a couple of them said they should have more than he gave them. Jones said he brought what was there, and that was that.

But that wasn't that. The rumors got to the point where Jones was denied entrance in the high priests, which, back then, was a political as well as priesthood leadership position. They cited his thievery as the reason. Moves began to be made by bishops to accuse Jones of the stealing, and women from the community were even telling Jones' wife to "leave him, and go find a better man."

On this matter, Jones writes: "My wife answered, "Well I will not leave Daniel Jones. I cannot better myself, for if he will steal there is not an honest man on earth." I always appreciated the answer."

It came to a head when Jones' (now many) accusers went to Brigham Young and sought a trial. Brigham Young met with Daniel W. Jones and told him that he had been accused, and asked him if he would stand trial and prove himself.

Jones describes himself as feeling shaken by this, because Brigham had previously looked over his account and approved of all he did, and expressed his satisfaction. But he agreed. He wanted to ask the prophet more questions, but Young turned away and went about some chores, not allowing him to speak.

Jones went into the trial nervous, afraid that there was nothing he could say to defend himself, if the prophet thought he was guilty. But the trial was a surprise to everybody. After asking everyone to testify, Brigham Young turned to Brother Jones and said (this is from the biography again):

"You wanted to ask me if I thought you guilty, but I gave you no chance to ask the question. I wanted you to learn that when I decide anything, as I had in your case, I do not change my mind. You were [121] not brought here for a trial for being guilty, but to give you a chance to stop these accusations." Then turning to my accusers again, "How does this look? After charging Brother Jones as you have, he makes a simple statement, affirming nothing, neither witnessing anything, and each of you say you believe he has told the truth. You have nothing to answer save that he is an honest man. Well, now, what have you brought him for?"

One of the complainers then asked if some of the company with me might not have stolen the goods. I answered "No; I am here to answer for all. Besides it would have been almost impossible for anyone besides myself to have taken anything unbeknown to others."

Bro. ______ asked, "If neither Bro. Jones nor the brethren with him have taken anything, how is it that I have lost so much?"

Brother Brigham replied, "It is because you lie. You have not lost as you say you have." (pp. 121, Forty Years Among the Indians).

After chewing out the accusers, Brigham Young and the quorum of the twelve wrote a letter of exoneration on Jones' behalf, asking that he be allowed into the high priests' counsel in Provo.

One more incident paints a perfect picture, to me, of who Daniel W. Jones was. Again, from Forty Years Among the Indians:

"One day I noticed a crowd of soldiers making some curious and exciting moves. I approached to see what was the matter. I saw an Indian standing, holding something in his hand and looking rather confused. The soldiers were getting a rope ready to hang him; all was excitement and I am satisfied that if I had not happened along the poor Indian would have been swinging by the neck in less than five minutes.

I could see from the Indian's manner that he realized something was wrong but could not understand why he was surrounded by soldiers.

I asked them what they were doing. They said that the Indian had brought one of their horses that he had stolen into camp and sold it for thirty dollars; that the owner of the horse was there and they were intending to hang the "d----d thief." I told them to hold on a minute, that I did not think an Indian would steal a horse and bring it into the camp where it belonged to sell. Some one answered, "Yes, he has; there is the money now in his hand that he got for the horse."

The Indian was still standing there, holding the money in his open hand and looking about as foolish as ever I saw one of his race look. I asked him what was up. He said he did not know what was the matter.

"What about the horse and money?"

He answered, "I found a horse down at our camp. I knew it belonged to the soldiers so I brought it up, thinking they would give me something for bringing it. This man," pointing to one, "came and took hold of the horse and put some money in my hand. It was yellow money and I did not want it. He then put some silver in my hand. There it all is. I don't understand what they are mad about."

I soon got the trouble explained. The man thought he was buying the horse, the Indian thought he was rewarding him for bringing the animal to camp; the owner happened along just as the trade was being made. Here ignorance and prejudice came near causing a great crime. As soon as this was explained I took the money and gave it back to the owner. No one had thought of taking the money. All were bent on hanging the honest fellow. Soon there was a reverse of feeling; most of the soldiers in the crowd being Irish, they let their impulses run as far the other way, loading the Indian with shirts and blouses. Some gave him money, so that he went away feeling pretty well, but he remarked that the soldiers were kots-tu-shu-a (big fools).

I have often thought there were many like these soldiers, " heap kots-tu-shu-a," in dealing with Indians."

Daniel W. Jones was a man who had a hard life, who was a survivor and hard worker, who was often thought to be odd by his neighbors. Throughout his life, he humbled himself and did what the prophets and other leaders asked of him in spite of tragedies, privations, and his own edge of pride and hot temper, which sometimes lead him to mouth off (but he always regretted it later, when he did). And somehow, all that rough exterior contained a soft heart, an open mind, and a view of the Indians as people who deserved justice just as the white men did.

Up Next: Four Hard Men, Four Different ways: Part II, Erastus Snow.

Oct 17, 2011

doing missionary work thru occupying countries

The other day I made a political comment as my facebook status update.

Always dangerous. But I couldn't hold it in. It was too much. I made my comment after reading this.

I'm not going to write here what my comment exactly was. Because I don't want that to be the focus of this post. Suffice it to say that old friends/family commented and it lead to a (genteel, but pointed) discussion about foreign policy.

I described my views as:

against military adventurism

against foreign entaglements

against spending more money on the military in a down economy (and here I'll modify and say, unless we've got a plan to pay for it that is concrete and can be enacted BEFORE the money is spent.)

And then this lead to a sort of side-discussion... that completely boggled my mind.

Did you guys know that there are people who think that having troops in Afghanistan/Pakistan/Egypt/Middle East and all sorts of other places...

qualifies as missionary work?

Did you know that there are people who think that, because there is an occasional afghani baby delivered by a US soldier on the ground in an undeveloped country, that this offsets the fact that we're there when we don't belong there, that we've killed thousands of civilians, and that all this must mean that we're making a good impression on said undeveloped country and making them want democracy?

Really?

Has nobody seen this?

or this?

or this?

How 'bout this.

You'll note that this last link directly refers to the wars in Iraq and the war on terrorism as causing "distaste" among those in the Muslim world.

Sounds like some great missionary work we're doing over there. I guess that is a traditional form of missionary work that has been practiced for thousands of years... back in the middle ages we called it the crusades. And before that, in the first century, it was the Muslim world who engaged in that kind of missionary work, converting millions to their religion by the sword.

Plus, when you think about it, that's a rather expensive mission, compared to the 10,000 or so it takes to send a church-approved missionary out into the field. How much more, I wonder, does it cost to send a US soldier into a battlezone, complete with equipment (including backup from tanks, drones, helicopters, etc?)

Sometimes when I talk to people, I realize that they don't really have anything. They just really really really want to believe something, so they find a reason to justify it. I mean, how else could someone actually believe that, when everything we hear from sources (and by sources, I don't mean comedians and talking heads like sean hannity, jon stewart, stephen cobert or glenn beck, and I don't mean slanted news sources such as fox news and yes, sometimes even NPR, I mean, real intelligence--when you go to their news websites and read their

The sad thing is, our soldiers could be good missionaries. If we used them the right way. If we did what it says to do in the Book Of Mormon--attack only when it's necessary to defend ourselves. I'd argue that it's possible to say that was the case, when we went into Afghanistan. But honestly, when you step back and think about it... why did we get involvedn Egypt? Why did we go to Iraq (other than the obvious reason... the Bush administration had a ve

ndetta that spilled over from the previous Bush administration.)

Since when do we go to war at the drop of the hat? Remember WWII, when the entire world was holding it's breath, waiting for America to join in, and it took a direct attack

on American soil for us to do anything about it?

What's happened since then?

I can see Afghanistan. Everything else seems pretty shady to me. And anybody who says we're in Afghanistan to do missionary work... let's just say I hope my tax dollars aren't paying for a crusade.

Just a little rant.

Always dangerous. But I couldn't hold it in. It was too much. I made my comment after reading this.

I'm not going to write here what my comment exactly was. Because I don't want that to be the focus of this post. Suffice it to say that old friends/family commented and it lead to a (genteel, but pointed) discussion about foreign policy.

I described my views as:

against military adventurism

against foreign entaglements

against spending more money on the military in a down economy (and here I'll modify and say, unless we've got a plan to pay for it that is concrete and can be enacted BEFORE the money is spent.)

And then this lead to a sort of side-discussion... that completely boggled my mind.

Did you guys know that there are people who think that having troops in Afghanistan/Pakistan/Egypt/Middle East and all sorts of other places...

qualifies as missionary work?

Did you know that there are people who think that, because there is an occasional afghani baby delivered by a US soldier on the ground in an undeveloped country, that this offsets the fact that we're there when we don't belong there, that we've killed thousands of civilians, and that all this must mean that we're making a good impression on said undeveloped country and making them want democracy?

Really?

Has nobody seen this?

or this?

or this?

How 'bout this.

You'll note that this last link directly refers to the wars in Iraq and the war on terrorism as causing "distaste" among those in the Muslim world.

Sounds like some great missionary work we're doing over there. I guess that is a traditional form of missionary work that has been practiced for thousands of years... back in the middle ages we called it the crusades. And before that, in the first century, it was the Muslim world who engaged in that kind of missionary work, converting millions to their religion by the sword.

Plus, when you think about it, that's a rather expensive mission, compared to the 10,000 or so it takes to send a church-approved missionary out into the field. How much more, I wonder, does it cost to send a US soldier into a battlezone, complete with equipment (including backup from tanks, drones, helicopters, etc?)

Sometimes when I talk to people, I realize that they don't really have anything. They just really really really want to believe something, so they find a reason to justify it. I mean, how else could someone actually believe that, when everything we hear from sources (and by sources, I don't mean comedians and talking heads like sean hannity, jon stewart, stephen cobert or glenn beck, and I don't mean slanted news sources such as fox news and yes, sometimes even NPR, I mean, real intelligence--when you go to their news websites and read their

The sad thing is, our soldiers could be good missionaries. If we used them the right way. If we did what it says to do in the Book Of Mormon--attack only when it's necessary to defend ourselves. I'd argue that it's possible to say that was the case, when we went into Afghanistan. But honestly, when you step back and think about it... why did we get involvedn Egypt? Why did we go to Iraq (other than the obvious reason... the Bush administration had a ve

ndetta that spilled over from the previous Bush administration.)

Since when do we go to war at the drop of the hat? Remember WWII, when the entire world was holding it's breath, waiting for America to join in, and it took a direct attack

on American soil for us to do anything about it?

What's happened since then?

I can see Afghanistan. Everything else seems pretty shady to me. And anybody who says we're in Afghanistan to do missionary work... let's just say I hope my tax dollars aren't paying for a crusade.

Just a little rant.

Oct 11, 2011

From Fort to Town: Building Provo

This is the post I've been waiting to do. I love the detective work that goes into figuring out an old town, and I love browsing through old photographs, and trying to capture a picture in my mind of places as they used to be.

So, let's talk about how Provo became a town.

After some more hostilities were exchanged between the settlers and the Indians, hostilities which later lead to the Walker War (yes, named after Walkera in my previous post, more on that later) Brigham Young advised the settlers to move in close to town and fortify the area with walls.

Provo was platted at this point. The surveying was done by many people, but Shedrick Holdaway and George Washington Bean, two people mentioned in previous posts, were a big part of this effort. After Brigham Young's instructions trickled down through the various settlements and into Provo, everyone began moving off the riverfront, out of the fields that spread out around the budding town, and clustered in close, buidling homes out of adobe bricks and logs along the newly-platted streets. A wall was began. It would eventually stretch along where 7th west is today, from sixth south to fifth north, east all the way to what we know today to be University avenue. The wall had a rock foundation 1 1/2 feet tall, and it ranged in height from 14-16 feet. It was six feet thick at the base, and contained bastions and portoles through which settlers could defend themselves from attacks. Fields and flocks were still kept outside city walls, in the fields that stretched off in all directions.

Back then, the streets of provo were known by letters (west to east) and numbers (north to south). The main thoroughfares were center street (or 7th, as it was called back then) and fifth west (then, J street.) Present day University Avenue was called "east main," then, and 2nd west, along which many of the principal families in town chose to build their houses, was called "west main."

Some of the first business and city buildings to be constructed were:

The sawmill, built by James Porter and Alexander Williams. This was located east of town, using the river out of the canyon as power.

The gristmill was built by James A. Smith and Issak Higbee (remember him? He was president of the first group of settlers to come to the valley) and was located inside town walls to keep the grain secure from theft. It used a "run," or large creek/canal that ran the western border of town.

The tannery was Bult by Samuel Clark. He produced the first leather in the fall of 1849. Apparently bark is needed, somehow, in the tanning of leather; this was taken from the pine trees growing in Provo canyon. There was no road back then, and so "A party of men and boys forced their way through the brush as far as Bridal Veil Falls, taking oxen with them." (from History Of Provo, Utah by Jens Marinus Jensen).

George A. Smith was the leader Brigham Young eventually appointed to oversee Provo City. The people of provo built him a fine brick house, very large especially for residences back then, in order to honor him.

According to lore, George A Smith refused the honor of living there. He said it was "too much for him," and that the city ought to use it as a gathering place. And so it was. The Seminary Building, as it was called, became meeting place for wards, for various official city business and counsels. And (as I tell in my story, Lightning Tree) this is the building that Judge John Cradlebaugh surrounded with a contingency of Johnston's troops and used as his "courthouse," during his brief occupation of Provo.

There was a bowery constructed in Town Square, which is now called Pioneer Park, and is located in the block of 5th West and Center Street. Just south of this, a tithing house was built, and under it was dug "the biggest cellar in the territory," to store the goods that settlers often used to pay tithing. The schoolhouse, made of logs, was located just north of the square, and just to the east was the Redfield/Bullock Hotel, which Harlow Redfield originally built, but was bought out by Bullock, who later became mayor of Provo, and was one of the men of the city taken by Cradlebaugh during the occupation earlier mentioned.

There were more buildings, mostly along the thoroughfares mentioned, and also strung out along 7th (now center) street. Sadly, none of these buildings still stand. At least not the ones I'm talking about, the ones built pre-1860.

Provo city was described in Eugene P. Moehring's Urbanism and empire in the far West, 1840-1890, as

"a city as well as a garrison....not just a thriving commercial center but a functioning strong-point." p.99

If this interests you at all, I would suggest these two sources for further reading, and to see some magnificent pictures that I could not provide in this post:

Provo, by Marylin Brown and Valerie Holladay

and the Provo City Library's digital collection of historical photographs, hosted by the Mountain West Digital Library

and

So, let's talk about how Provo became a town.

After some more hostilities were exchanged between the settlers and the Indians, hostilities which later lead to the Walker War (yes, named after Walkera in my previous post, more on that later) Brigham Young advised the settlers to move in close to town and fortify the area with walls.

Provo was platted at this point. The surveying was done by many people, but Shedrick Holdaway and George Washington Bean, two people mentioned in previous posts, were a big part of this effort. After Brigham Young's instructions trickled down through the various settlements and into Provo, everyone began moving off the riverfront, out of the fields that spread out around the budding town, and clustered in close, buidling homes out of adobe bricks and logs along the newly-platted streets. A wall was began. It would eventually stretch along where 7th west is today, from sixth south to fifth north, east all the way to what we know today to be University avenue. The wall had a rock foundation 1 1/2 feet tall, and it ranged in height from 14-16 feet. It was six feet thick at the base, and contained bastions and portoles through which settlers could defend themselves from attacks. Fields and flocks were still kept outside city walls, in the fields that stretched off in all directions.

Back then, the streets of provo were known by letters (west to east) and numbers (north to south). The main thoroughfares were center street (or 7th, as it was called back then) and fifth west (then, J street.) Present day University Avenue was called "east main," then, and 2nd west, along which many of the principal families in town chose to build their houses, was called "west main."

Some of the first business and city buildings to be constructed were:

The sawmill, built by James Porter and Alexander Williams. This was located east of town, using the river out of the canyon as power.

The gristmill was built by James A. Smith and Issak Higbee (remember him? He was president of the first group of settlers to come to the valley) and was located inside town walls to keep the grain secure from theft. It used a "run," or large creek/canal that ran the western border of town.

The tannery was Bult by Samuel Clark. He produced the first leather in the fall of 1849. Apparently bark is needed, somehow, in the tanning of leather; this was taken from the pine trees growing in Provo canyon. There was no road back then, and so "A party of men and boys forced their way through the brush as far as Bridal Veil Falls, taking oxen with them." (from History Of Provo, Utah by Jens Marinus Jensen).

George A. Smith was the leader Brigham Young eventually appointed to oversee Provo City. The people of provo built him a fine brick house, very large especially for residences back then, in order to honor him.

According to lore, George A Smith refused the honor of living there. He said it was "too much for him," and that the city ought to use it as a gathering place. And so it was. The Seminary Building, as it was called, became meeting place for wards, for various official city business and counsels. And (as I tell in my story, Lightning Tree) this is the building that Judge John Cradlebaugh surrounded with a contingency of Johnston's troops and used as his "courthouse," during his brief occupation of Provo.

There was a bowery constructed in Town Square, which is now called Pioneer Park, and is located in the block of 5th West and Center Street. Just south of this, a tithing house was built, and under it was dug "the biggest cellar in the territory," to store the goods that settlers often used to pay tithing. The schoolhouse, made of logs, was located just north of the square, and just to the east was the Redfield/Bullock Hotel, which Harlow Redfield originally built, but was bought out by Bullock, who later became mayor of Provo, and was one of the men of the city taken by Cradlebaugh during the occupation earlier mentioned.

There were more buildings, mostly along the thoroughfares mentioned, and also strung out along 7th (now center) street. Sadly, none of these buildings still stand. At least not the ones I'm talking about, the ones built pre-1860.

Provo city was described in Eugene P. Moehring's Urbanism and empire in the far West, 1840-1890, as

"a city as well as a garrison....not just a thriving commercial center but a functioning strong-point." p.99

If this interests you at all, I would suggest these two sources for further reading, and to see some magnificent pictures that I could not provide in this post:

Provo, by Marylin Brown and Valerie Holladay

and the Provo City Library's digital collection of historical photographs, hosted by the Mountain West Digital Library

and

Oct 4, 2011

Utah Valley and the Gold Rush

A few of the details I didn't mention in my last history blurb on the Battle of Fort Utah (or as it is sometimes called, the Battle of Provo River):

a) Cheif Old Elk was chief of the Timpanodos or Timpanoges tribe (sorry for the confusion, there)

AND

b) One of the big advantages the settlers had in the conflict following Old Bishop's demise was a reprieve: a large party of emigrants were traveling through Utah Valley right as the chief's body was discovered, in February of 1849. They were headed to the California Gold Fields. With so many "white men" in the valley at the time, the Indians didn't dare engage the settlers in conflict.

The gold rush and the Mormons go hand in hand. One made the other possible in a sense... and that's in both directions. To explain what I mean, let's go back a little ways, to the construction of the first fort, and also further back, to discuss a group of Mormon settler men who volunteered to help the US army engage in a conflict taking place in the far west. I'm talking about the Mormon Battalion, of course.

First things first. A man we haven't mentioned yet, but who was amongst the first to arrive in Utah Valley: Jefferson Hunt.

He's much older in this picture than he is in the story I'll be telling you.

Here's an interesting account of the building of Fort Utah, from a book called "Brigham Young the Colonizer." If you're interested in the history of the colonization of Utah and the prominent men and women involved, this is a great read.

Jefferson Hunt along with Issak Higbee and his two counselors, were the first to arrive in Utah Valley of the thirty families sent there. They immediately began work on the fort.

From Brigham Young the Colonizer, p. 214:

The fort consisted of a stockade closing a parallelogram, “about twenty by thirty rods, enclosing and ancient mound near the center. The outer walls of east, north, and west sides of the fort were composed mostly of cabins built of cottonwood logs in a continuous line. Pickets twelve feet high were set solidly together to form the south wall and to fill any spaces between cabins. Light was admitted into each cabin through two windows—one at the back and one at the front. Coarse cloth was used to cover the windows, as the settlers had no glass. On the mound in the center of the fort, a bastion, or raised platform about fifteen feet high, was erected. A twelve pound cannon was placed on this bastion and fired on different occasions in order to impress the natives with a proper respect. A corral was built on the east in which the cattel were kept at night. In addition to this general stock corral, private corrals were built behind the respective cabins with gates or back door openings.

*interesting sidenote* the mound mentioned here, that the fort was built around, already existed when the settlers began constructing. As it is described as "ancient," one wonders if there were artifacts/signs of an Indian burial ground here.

Fort Utah was built in 1848, the year the men from the Mormon Battalion returned to meet their families in the valley. The men were actually discharged in 1847, but Brigham Young sent them a letter as they were about to head east to join the saints, that unless they had "sufficient food and supplies" to last the winter, they should stay in California and work through the winter, and come out in spring of 1848. 150 of the men continued toward the valley, and 100 stayed behind, most of whom found work in a fort owned by a man named John Sutter--work such as tanning, blacksmithing, and building two mills.

It was the six former battalion men who built the sawmill who participated in the discovery of gold that started the California gold rush—recorded in the journals of two Battalion members, William Bigler and Azariah Smith. And there's another Mormon Connection to the discovery of gold in the area: when Sidney Willis and Wilford Hudson, also Battalion members, heard rumor of the discovery at the sawmill, they went to check things out. On the way back to their work, they discovered gold themselves, in a place called Mormon Island which became one of the most profitable sites during the gold rush. Interestingly enough, neither of them was much interested in starting an operation there; it was later companies whom they agreed to guide to the spot who were made rich by the discovery.

Pictured here are (from right to left) Henry Bigler, Azariah Smith,William J. Johnston and James S. Brown. I kind of like the look of Azariah Smith, don't you? And what a name.

Information on the finds leaked, of course, and the California Gold Rush started.

When the battalion men couldn’t leave when they planned because of the heavy snows in the sierras, they instead took on a project to blaze a trail over the mountains which was later called the “Wagon Freeway.” This was the route that most everybody took to get through the mountains and down into the fertile, gold-veined foothills and valleys of California.

Jefferson Hunt (remember, we were talking about him) was a part of that effort. After helping to Settle Provo, he offered himself as a hired guide to countless emigrant parties who traveled south, down through Utah Valley to Southern California.

There were a few different routes of the emigrant trail, which lead through the new LDS colonies and west to California. The oldest involved something you've probably heard of called the "hastings cutoff." This was used in the year of 1846. It ran through the weber river over the Wasatch mountains. Another branch cleared a rough trail down Emigration Canyon to get into the SL valley, pioneered by the now-famous Donner Party.

Then in 1847 there was the Mormon Trail, which went from Fort Bridger to Salt Lake city, (a brand new city! Remember, it was only settled in 1846.) Salt Lake City was a boon for the travelers. They could stop, get repairs and trade or pay cash for fresh supplies. The route led northwest out of Salt Lake City, north of the Great Salt Lake for about 180 miles before rejoining California trail near the city of Rocks in Idaho. This route, unlike the previous one, generally provided adequate water and grass. Thousands used this for years.

The trail that went south through Utah valley was the Mormon Trail to Southern California, which was opened when former Mormon Battalion soldiers began traveling between southern California and Salt Lake City, starting around 1847. The trail went from Salt Lake City, Utah, down through Utah Valley, and traveled the chain of Mormon settelments until St. George Utah; from there, it ran to Las Vegas, Nevada, and then to Los Angeles, California. You can see both on the map below.

The new Mormon colonies provided an easier route to California, because they were little oases of supplies, trade, and access to health care and other necessities in the middle of what was once a desolate, trecherous route. And the trade of the emigrants helped the pioneers--particularly those in Fort Utah, that very first year after its establishment--to survive, and to have the means to grow and establish good routes of travel and communication.

And (not coincidentally) it was a group of Emigrants traveling this southern route who became the victims of the infamous Mountain Meadows Massacre, which I use as an important piece of backstory for my novel, Lightning Tree.

a) Cheif Old Elk was chief of the Timpanodos or Timpanoges tribe (sorry for the confusion, there)

AND

b) One of the big advantages the settlers had in the conflict following Old Bishop's demise was a reprieve: a large party of emigrants were traveling through Utah Valley right as the chief's body was discovered, in February of 1849. They were headed to the California Gold Fields. With so many "white men" in the valley at the time, the Indians didn't dare engage the settlers in conflict.